Don’t Get Sucked Out to Sea

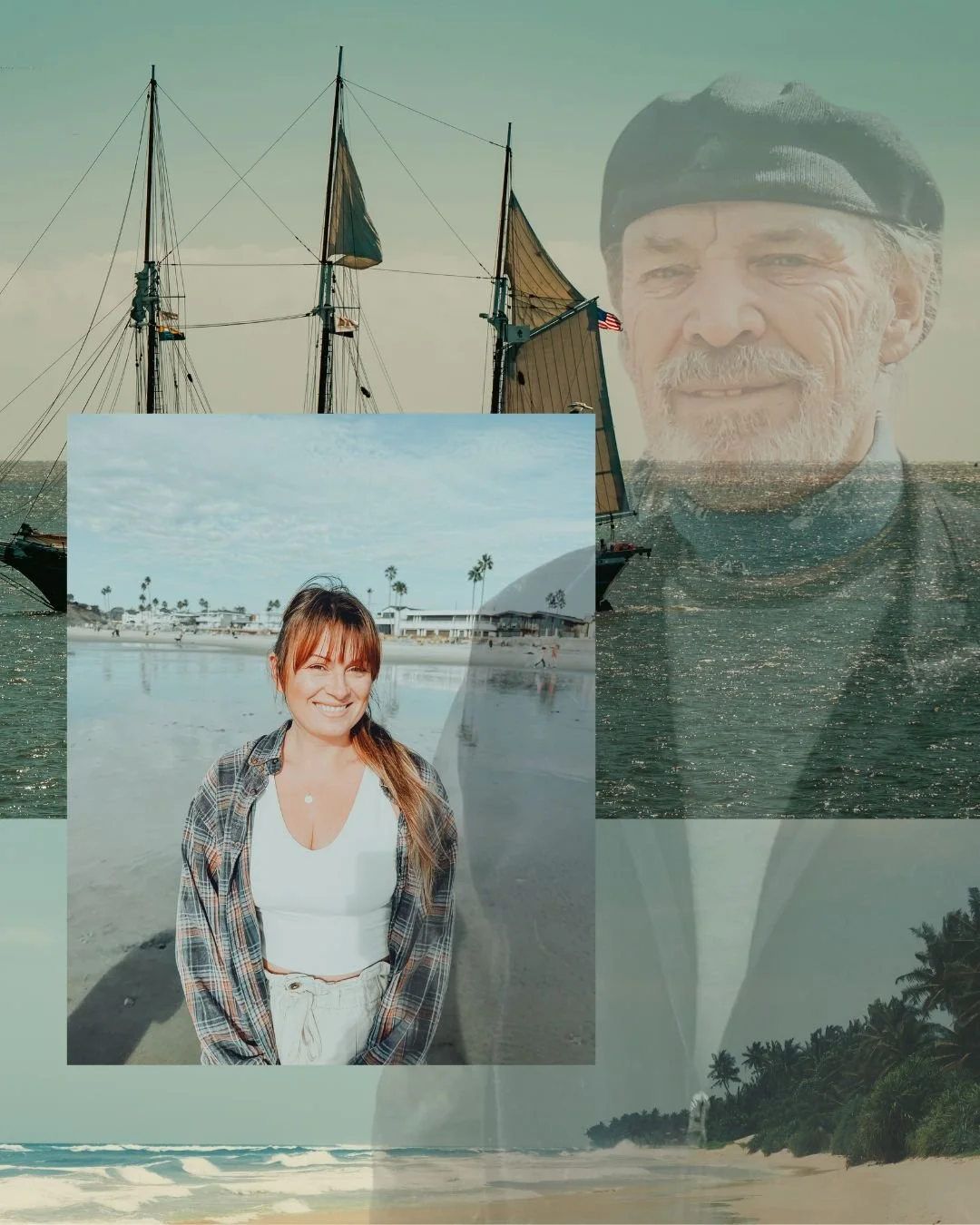

Don’t Get Sucked Out to Sea. Digital Collage

In the simplest terms, grief is just the reflection of love. The infinite hollowness of grief is equal in shape, size, and intensity to the infinite fullness of love. The absolute, steady, grounding anchoring of love is only equal to the complete unmooring of grief. So when I found myself awkwardly sobbing to a new doctor, trying to explain my medical history, or scrolling the depths of the internet until I was unable to stay awake—just to avoid another night of crying myself to sleep—the one little glimmer of hope, of peace, was this idea: if we want to avoid the torturous suffering of grief, we must also renounce and declare amnesty from the one true purpose of living, which is to love.

Experiencing the death of my father in the midst of early motherhood created a polarizing emotional turmoil that split me in two. On one hand I was depressed and consumed by primal sadness; on the other I was flooded with joy and the most elemental euphoria. With this juxtaposition came insurmountable fear—fear and proof that this all-consuming love had the potential to become an all-consuming grief. And that realization, that paralyzing fear, ruled over me in many ways for a time. My dad had made his peace, but I had not. I still haven’t. I still want him to be here, to spend time with him and hear him laugh. I want my kids to know him. I want more time.

When he left, I couldn’t feel him around me. He was really and truly gone. In my chest I knew he was free and had let this place go. But finally he started coming to me in dreams. The first time it happened was about six months after he passed. He said, “Hey, Mel.” He told me that he had found a place “under the rafters” where he could “make a call,” and that’s exactly what it felt like—like he was calling me from some galactic phone booth to say hi. I woke up with the first real sense of peace I’d felt in a very long time. And whatever you believe, I think there is a part of us all that has to believe that even our most proven scientific realities are miracles.

The next time he came to me in a dream, it was to give me some really good advice. In this dream I was on a ship. Both of my parents were there, and they were calm. I was walking when my dad said, very matter-of-fact, “Don’t get sucked out to sea.” And that’s when I realized that half of the ship was missing. When I woke up, I was overcome with the clarity of his words. Water typically represents emotions in dreams, and if grief doesn’t feel like a deep, vast ocean, I can’t think of a better metaphor. So this poignant advice from him—or the part of him that still exists in my subconscious—was very clear: Don’t let this grief drown you. You have to keep living. Stay on the ship. Don’t get sucked out to sea.

As the years go on, I have gotten better at coping. I only think about him 100 times a week instead of 1,000, but his loss is felt daily. The absence of him has become a permanent part of me. Unfortunately, this is part of my identity now. But I wouldn’t give up the love to spare me from the grief.